The Hunted: Tracking Uzbekistan’s long arm

For Foreign Policy:

Uzbekistan’s president has jailed, tortured, and murdered his opponents at home. Now, he’s hiring hit men to track down and kill dissidents abroad.

ISTANBUL — A cold drizzle fell on Istanbul on the morning of Dec. 10, 2014, as Abdullah Bukhari made his way to teach his students at a madrasa nestled amid apartment blocks and hardware stores in the Zeytinburnu neighborhood. A white prayer cap on his head, Bukhari made two crucial departures from his daily routine, according to one of his students: He told his bodyguard to stay at home and he didn’t wear a bulletproof vest beneath his white ankle-length thobe.

Two security cameras captured what happened: As Bukhari waited for someone to let him into the madrasa, he glanced to his left, settling for a moment on a clean-shaven man in a black winter cap and blue jeans, both hands tucked inside the pockets of a black jacket.

Three months earlier, the 38-year-old Bukhari had been told he had a price on his head. Two former Chechen rebels living in Istanbul had learned that the Uzbek imam was on a list of assassination targets — men wanted for their opposition to Islam Karimov, the president of Uzbekistan. Bukhari took the news well. “If Allah wants me dead, I will die,” he told one of his students.

Bukhari looked away and the man in the black jacket got his chance, shoving the silencer of his 9 mm handgun between the imam’s shoulder blades. A puff of smoke appeared. The gunman bolted down the street as Bukhari stumbled into the madrasa, dying shortly thereafter.

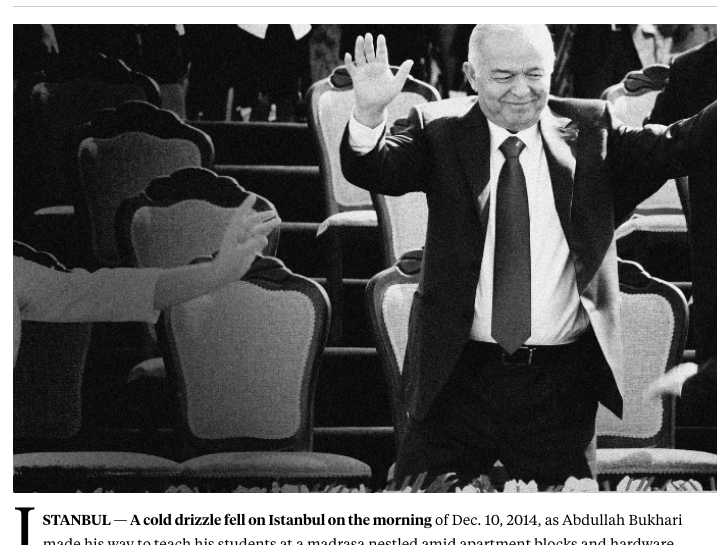

The long arm of Islam Karimov had caught up with him.

Since settling in Turkey 12 years earlier, Bukhari had opened five madrasas across Istanbul and developed a sizable following among the city’s conservative Central Asian diaspora. His students numbered in the thousands, and included Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Chechens. Well-versed in Islamic law and theology, Bukhari used his sermons to extoll the virtues of jihad against Vladimir Putin in Chechnya and Bashar al-Assad in Syria. The imam welcomed the widows of Syrian rebels — Arabs and Central Asians alike — with open arms, offering them financial support and holding them up as an example for his students of sacrifice for jihad.

Bukhari also called for a movement to bring down Karimov. The 77-year-old former Communist Party boss is the only ruler Uzbekistan has known since gaining independence in 1991. Karimov has held onto power by imprisoning thousands of opponents, accusing many of being Islamic extremists. More recently, he has fingered his opponents as supporters of the Islamic State.

The Uzbek president’s unrelenting pursuit of his critics has pushed peaceful opposition out of the country. For a man known to boil his critics alive, a usurper lurks around every corner. He has even imprisoned his globe-trotting, pop-singer princess of a daughter, Gulnara Karimova. On March 29, Karimov was re-elected to a fourth term, the second time he violated a constitutional two-term limit. Western observers criticized the election, in which the president won more than 90 percent of the vote, with a turnout of 91 percent.

Pious old Uzbek dissidents pray for the president’s life to end, while others hone their skills as jihadis in conflicts across Asia and the Middle East. In the last decade, thousands have joined militant groups fighting in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and over the last few years, hundreds of battle-hardened Uzbeks have joined the Islamic State in its effort to establish a theocracy in Syria and Iraq. Many of the Uzbek jihadis have teamed up with Chechen rebels who hold Russian passports.