Why Baba Jan Won

For Tanqeed.org:

GAKUCH, PAKISTAN — June 10, 2015 – Getting to Baba Jan was not an easy task on election day in Gilgit-Baltistan.

Everything seemed fine as I handed over my belongings to the guard at the Damas jail in Ghizer district, until the prison’s deputy superintendent ran towards me. “I am sorry, but I do not want to get in trouble. This is a very sensitive issue and you need to get permission from the district commissioner.” So began a game of cat and mouse trying to track down the D.C. through a network of evasive police officers and civil servants.

“Sir, I cannot disturb the D.C. now, he is sitting with a brigadier and a colonel,” one police officer told me before offering to attempt conveying my request for an interview with Baba Jan through the DC’s personal cook. It didn’t work.

It took several more tries before I was finally granted permission to speak to the man himself.

An electoral fight

Gilgit-Baltistan has served as a staging ground for several attempts to capture territory from India in neighboring Kashmir. Claimed by both India and Pakistan, Gilgit-Baltistan’s two million residents live in a legal limbo tied to the resolution of the larger issue of Kashmir. While locals can be elected to seats in the Gilgit-Baltistan Legislative Assembly (GBLA), the body has almost no real powers. Most of the region’s budget, including hundreds of millions of dollars worth of customs fees from trade with China, sits with the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Gilgit-Baltistan. Instead of appealing to Pakistan’s higher courts, locals deal with a set of courts staffed by federally-appointed judges and civil servants.

In the weeks leading up to the elections, the entire spectrum of political personalities had dropped into Gilgit-Baltistan, a fact overlooked by the local Pakistani media for whom Gilgit-Baltistan is mainly a story a bout a regional power struggle between India, Pakistan, and China. Nawaz Sharif came and touted the Pakistan-China economic corridor. Imran Khan flew in to call the prime minister’s visit “pre poll rigging.”

Thousands of regular army soldiers and Rangers had been deployed alongside the Gilgit Scouts on election day. They sped along the narrow roads running along raging rivers, past a smattering of flags from the political parties contesting elections: the JUI-F, the PTI, the PPP, and the PML-N. In the Ghizer district government’s control room, the staff served cold drinks to army officers and made phone calls to local media to make sure they stayed on point: “The polls are completely peaceful and there will be no rigging.”

Alongside the mainstream parties, two hundred independent candidates, and a few nationalists threw their hats into the mix for the 24 seats up for elections. Baba Jan is among them. He ran for the GBLA in elections on June 8th contesting as a candidate of the Awami Workers Party (AWP) because he wants to see more self-rule in Gilgit-Baltistan rather than the legal limbo in which it currently sits. And, Baba Jan knows the Kafka-esque bureaucracies of the legal system here well: He has been sentenced to life in prison by an anti-terrorism court, accused of participating in political riots in 2010 that destroyed dozens of government buildings in Hunza.

It is a strange thing to contest the elections for nationalists like Baba Jan, who on previous visits I made to the region, had not shied away from telling me the GBLA was an inconsequential body.“If you talk about our constitutional rights, you lose votes. Very few people here understand the constitutional rights issue,” Nazir Ahmad, a lawyer contesting from Ghizer told me when I asked him why he set aside his nationalist tendencies to run for office. “We nationalists are contesting the elections because we hope it will mobilize people. We no longer believe the masses can topple the system. It must be changed from the inside now.”

In the end, the nationalists largely lost, the notable exception being Nawaz Khan Naji, a leader of the Balawaristan National Front, whose village of Sherqilla opted to reelect him.

Baba Jan himself came in second in his district, drawing more than 4,500 votes, a massive victory for a candidate running from inside jail. But, those votes could not surpass nearly 9,000 votes pulled in by Ghazanfar Ali Khan, the Mir of Hunza. Khan, a member of the PML-N, has served seven terms in the GBLA, including as the region’s first chief minister.

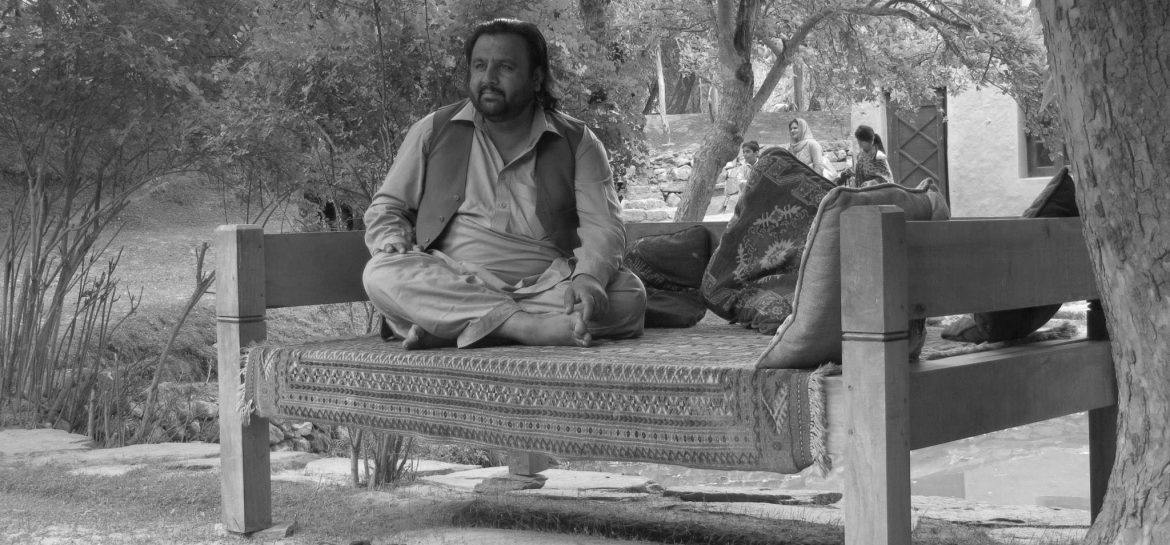

“The Mir is the latest in a 980 year line of rulers,” an upbeat Baba Jan told me in his cell the morning after the elections. “I asked the D.C. if I could record a video message for my campaign, and I wasn’t even allowed to do this.”

Jan may have lost the elections, but his campaign, financed and organized by residents themselves, has had an impressive degree of success. Students, women, and Awami Workers Party members from across Pakistan helped put together Baba Jan’s campaign. “I only spent 280 Rs. from my own pocket,” Jan said as he took a break from advising other prisoners on how to deal with their own legal troubles in order to speak with me. “It’s a new era now for the people here, we fought a civilized campaign. In a country where women are not allowed to vote in some places, women in my campaign went door to door, they setup their own offices, they held their own rallies.”

That Jan galvanized as many votes even while in prison is an impressive feat that speaks to the situation in Gilgit-Baltistan and how shows how many people are behind him. Even as Jan lost, he won: indeed, for many, the number of votes he was able to get are the critical story of this election.

“He does not act like an important person,” Tausif, a Baba Jan supporter said. “He sits on the ground with people, and is ready to meet anyone who needs him. All the youth are voting for him because he has done so much work for people, especially for the Attabad affected.”

Tausif was referring to an incident in June 2010 when a landslide blocked the Hunza river at Attabad village, creating a 22 kilometer long lake that submerged the Karakoram Highway linking Pakistan and China—along with the homes of 25,000 locals. The federal government, at the time led by the PPP, promised compensation for the displaced and a plan to drain the lake and return residents to their homes.

Yet, more than a year after the landslide, a few dozen families had yet to receive any compensation for their losses, so they organized a sit-in to block the road through a nearby town, Aliabad. In the ensuing state action to clear the protesters, a father and son were gunned by police. The next day, thousands of locals set fire to dozens of government buildings across the district, sparking mass arrests. More than 100 people, including Baba Jan, were arrested and faced the prospect of a trial in an anti-terrorism court for charges that included sedition.

When I visited Aliabad in June 2014, dozens of families were still living in shelters paid for by the U.N. Development Program and the Agha Khan Fund. Many of the displaced had made a living from small farms, built on terraced land along the river bank that was now submerged. The $6,000 given to each family had long run out.

Baba Jan explained to me why it had been important to protest against the conditions in Aliabad, demonstrations that put him in jail. “The PPP first said they would complete the work in 15 days, then in 35 days, then in 3 months,” Baba Jan said. “Then [PPP leader Kamar Zaman] Kaira flew up here with the Governor and the Minister of Kashmir, they called a bunch of bulldozers and machines and didn’t do anything and flew away.”

In the end, part of the reason Baba Jan lost the election seems to be concern from residents he would not be able to secure anything for them from Islamabad. “We are completely controlled by Islamabad, and the PML-N is in charge there,” one resident told me. “If a candidate has no one [supporting him] in Islamabad, what is he going to be able to do?”

A legal limbo

Of those arrested in 2010, 36 people had been charged by anti-terrorism courts by June 2014. Last September, a judge finally announced the verdict in the remaining cases, handing multiple life sentences and fines totaling more than 6 million Rs to Baba Jan and 11 other activists.

One of Baba Jan’s life sentences was thrown out earlier his year, but he is still appealing the other in a case where he is accused of burning down the house of a police officers. “I was forty miles away when that happened,” Baba Jan told me. According to Jan and his lawyer, the police officer whose home was burned down has said in court that he registered the case against Baba Jan based on the word of an informant, who he was not willing to identify. The officer’s son, who was home at the time of the fire, has told the court Baba Jan was not among the people he saw setting the fire.

“The court should see that so many peaceful people gave us their votes, [me and the others accused] are not terrorists, we are democrats, we are peaceful people,” Baba Jan said. “Otherwise why would I be fighting an election?”

Baba Jan’s legal troubles are in fact part of a larger effort by Islamabad to control resentment in Gilgit-Baltistan. Hundreds have been charged by anti-terrorism courts here in the last few years over political protests. Last April, hundreds of thousands held an 11-day sit-in in Gilgit city after Islamabad threatened to withdraw a subsidy on wheat, the last remaining of 122 subsidies promised to residents by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1972. Bhutto made the concession in an attempt to match similar subsidies being granted in Indian-controlled Kashmir.

This February, 19 people who spoke at a conference entitled “Gilgit-Baltistan in the Light of Kashmir Dispute” were charged with sedition.

The level of political violence seen in Gilgit-Baltistan pales in comparison to what is seen in most of the rest of the country. In the eyes of Islamabad, Baba Jan and the other nationalists stand in the way of Pakistan’s regional strategy of allying with China against India. The Aliabad protests in 2010, for instance, threatened the heart of the much-touted China-Pakistan economic corridor, literally blocking the route. And, calls for greater powers for the GBLA complicate the status of Kashmir: if Pakistan grants Gilgit-Baltistan the status of a province, it tacitly approves India’s efforts to do the same in Srinagar.

In the days leading up to the elections, seven activists were arrested as they attempted to deliver a statement that called the elections “illegal” to U.N. observers office near Gilgit city. For Islamabad, the nationalists’ rhetoric sounds perilously close to that of India. The statement of these activists came after recent remarks by the Indian Foreign Ministry that Pakistan was using the elections to “camouflage its forcible and illegal occupation” of the region.

“Delhi has no business telling us what to do here,” Baba Jan said when I asked him why India had become so vocal about the elections. “They are killing people in Kashmir for asking for their rights, they are bombing the Naxalites, they need to fix their own house.”

“And Islamabad needs to resolve our issue and that of Kashmir. They need to give the people here their basic rights too.”