Islamabad looks to clear settlements housing tens of thousands displaced by conflict

For FSRN:

Listen to the story:

After mass protests, officials in Pakistan’s capitol of Islamabad have postponed plans to evict nearly 80,000 people from unrecognized settlements there. Many of the residents are ethnic Pashtuns from the region bordering Afghanistan. Some blame Pashtuns for the Taliban insurgency that has killed tens of thousands of Pakistanis. Officials want to clear the shantytowns, saying they are safe havens for militants. But residents say they are the target of scapegoating and ethnic tensions.

Umar Farooq reports from Islambad.

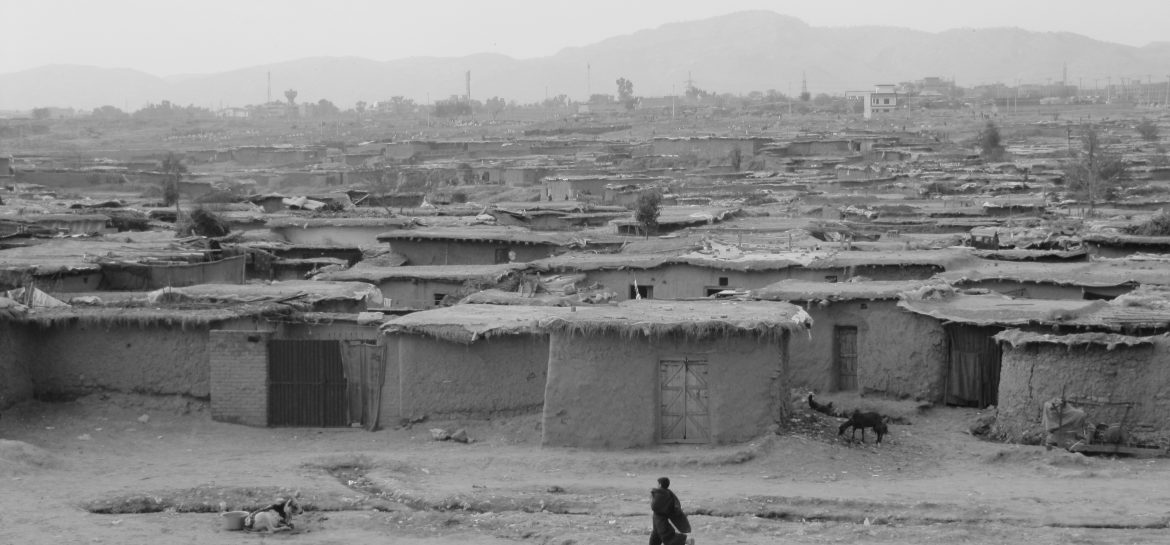

Thousands of residents of Islamabad’s slums are protesting plans to level their homes in settlements which stick out like a sore thumb of poverty in Pakistan’s otherwise glitzy capital city. The walls of houses are made of dirt and the roofs are made of straw. There is no electricity and no plumbing. The land is owned by the government and has an estimated worth of hundreds of millions of dollars.

“They want to destroy these settlements – some even have Christians living there – because they say they are terrorists,” says Mariam Bibi, who works as a maid and lives in one of the shantytowns slated for demolition. “There aren’t any terrorists there, the terrorists are the ones in power, the ones ruining the country. We are sweepers, laborers, hard working people, not terrorists.”

Police regularly raid the settlements, detaining hundreds of people, only to release them the same day. The last operation came after a March third attack on the city’s district courts. Two suicide bombers killed eleven people, renewing calls for eradicating the slums, which the Interior Ministry claims provide a safe haven for militants.

Security experts and the Islamabad police say that’s not true. According to police officials, no terrorist attack has ever been linked to the slums.

Twenty-two year old Muhammad Yaqub lives in Islamabad’s Afghan Basti settlement. He says he was born here but isn’t sure when government authorities will come to demolish his home. He received an order to leave by March 24th.

His family is from Bajaur Agency, in the tribal belt near the border with Afghanistan. The settlement he lives in, called Afghan Basti, was first set up in 1979 to house Afghan refugees from the Soviet invasion. By the American invasion in 2001, more than two decades of conflict had prompted nearly four million Afghans to move to Pakistan, where many lived in ad-hoc settlements like Afghan Basti.

When a Taliban insurgency formed in Pakistan, those Afghans became increasingly unwelcome.

Pakistan planned on deporting around 1.7 million remaining Afghan refugees two years ago, but after intense international pressure, it delayed those plans until 2015.

Today, only a few hundred of Afghan Basti’s 8,000 residents are Afghan. Most are Pakistanis, ethnic Pashtuns like Muhammad Yaqub, who come from the tribal belt near the Afghanistan border. Cultural ties between Pashtuns on both sides of the border meant it was easiest for migrant workers to live in settlements like Afghan Basti.

“We are Pakistani citizens but the Pakistani government claims this is an Afghan settlement,” says Badir Shah. He has lived in Islamabad since 1986, after migrating from Swabi, in the country’s north west. “If this is an Afghan settlement, why are we asked for our votes every five years? We have our own polling station and they claim we are illegal people and not genuine Pakistanis.”

Like millions of other Pashtuns, Shah’s family left their homes decades ago looking for a better life. They can’t return because of fighting between the Taliban and the military.

Shaista Sohail, the Islamabad official overseeing the slum eradication program, says the residents are a security threat. Many of the settlements’ residents work in the Sabzi Mandi, the city’s sprawling produce market. Officials say if the residents cannot afford to rent homes, they should return to their villages in the tribal areas.

“If you live in a rented accommodation, whether it’s one room accommodation, you don’t let everyone in. You have certain rules and regulations,” says Sohail. “So the level of crime is much lower, whereas if you go to such a place, where all kinds of clandestine activities are rife. These people, who are earning much more fetching carrying in the Mandi and doing small businesses of their own, how come they can’t afford rented accommodations? So if they cant, they have to go back to their villages.”

None of those options make sense to residents though. Muhammad Yaqub says if he earned enough money, he would have left the settlement on his own by now. “I don’t have a steady income,” says the fruit vendor.

“Sometimes it sells well, sometimes it sells badly. Sometimes we get a good day’s wage, some days not. That’s how we make a living. That’s our routine.”

Officials have said they postponed the evictions, originally slated for March 24th, in order to allow for a polio vaccination campaign in the settlements. Residents say they are ready to face bulldozers whenever the city decides to begin its operation. That could happen as soon as as this week.